Improvisation

By Duncan Kennedy

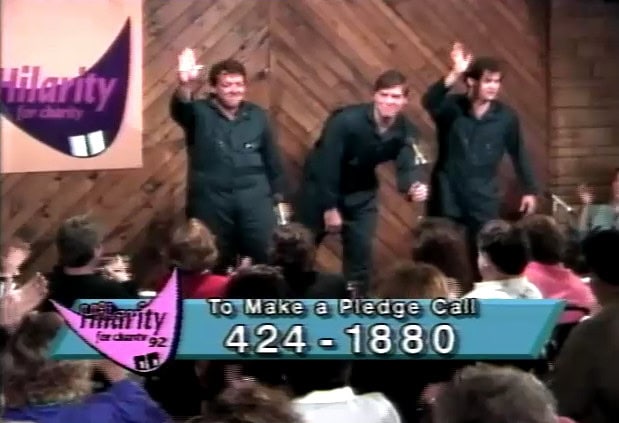

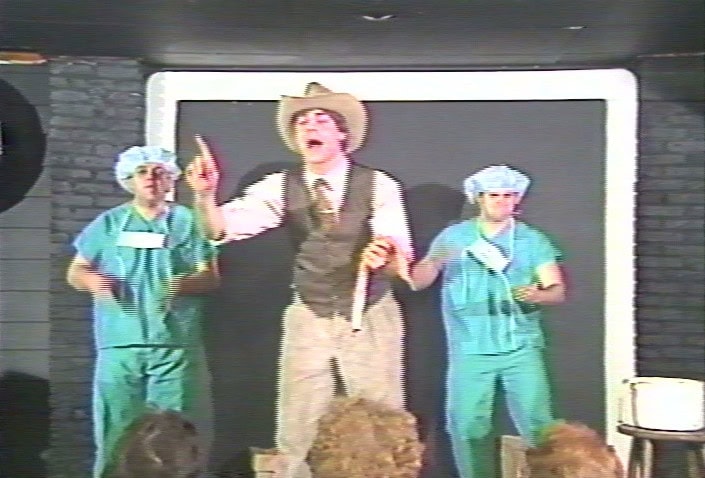

In an early chapter of my life that was several decades ago, I was a writer and performer in a comedy group in Western New York. We had been at it for several years with some modicum of success doing sketch comedy at clubs and colleges across the northeast when a club owner suggested that we look at adding some improv to expand the act and solidify us as bankable headliners.

We had taken a few acting classes and participated in some improv workshops to improve our stage presence as performers, but most of our act were spoofs and scenes we had written, rehearsed, and then performed live on stage at comedy clubs, theater stages, or college unions. However, most of what we came up with originated from either individual spontaneity or collaborative humorous play, so we figured that “doing improv” would be pretty straight-forward for us.

Over the following weeks and months that we delved into the world of live performance improve, it quickly became apparent that we were over our heads. Yes, we were reliably funny, but the nuance of putting on a “good show” while doing it was fairly elusive. Transitioning from polished comedy sketches, silly gags, and odd character monologues into the more freeform realm of performing without a script was pretty trying at first. We would be talking over each other, skipping through situations, and often riding a manic high to try and successfully close on a big laugh. We needed help.

So, we did what everyone did prior to the Internet during the late 80’s/early 90’s. We went to the library and found Viola Spanolin’s book Improvisation for the Theater based on a recommendation from a local actor/stage director. Being the terrible students we were, we skipped past all the instruction details and directions and went right to the descriptions of improv games to see what we could poach for the stage. Unfortunately, most were exercises for how to get in character, feel more comfortable on stage, and better relate/connect/interact with your fellow performers. So we did what we always did best back then and quickly came up with a game making fun of all those exercises like freeze tag, jumping around with emotions, and fill in the blank. While we had a blast doing it, it was not always a crowd pleaser, and often whenever something worked, in a panic we’d do it again the following night to ensure walking off-stage to a roaring ovation. Not improv at all.

That’s when we realized that improvisation was not about saying something funny on the spot, off the top of your head. That’s what the audience sees. Improvisation – at least in terms of being successful on stage to make a paying audience laugh – was about structure. That’s what the performers need.

Once we had crossed that bridge, we were off and running. Much like jazz, we’d agree on a starting key, time signature, and tempo and then make everything else up from there. There was an unspoken pacing, a groove, in terms of when to speak and when to listen that ensured whatever was happening on stage fluid and flowing – much like a 16-bar solo. There were non-verbal signals to each other when we had an idea we wanted to run with, or, thankfully not as often, when we were stumped and needed prodding. The cardinal rule was always, “Yes, and…” Never shut down a train of thought, conversation, or situational flow by closing off the next opportunity. If it wasn’t funny, we could just move on to something that was. Many times, something not being funny was actually a good crowd pleaser.

One of our more successful improv bits was “The Penalty Game” where the audience would shout out a topic and we had to come up with either a limerick, a 3-line rhyme, or a knock-knock joke. If what we said was funny, great! If not, we’d have to do push-ups right there on the stage. Either way the audience was laughing and enjoying the show as we stuck our necks out only to then fall to the floor if we failed. We always worked clean, so we did our best to work around the blue and scatological. Hence the time we got “planets” and worked our way around the solar system without giving into the easy laugh and mispronouncing our second farthest planet. My personal favorite was once when someone shouted out “microwave ovens.” Without skipping a beat, I started a knock-knock joke with “Amana” and then closed with the longest palindrome I knew “A man a plan a canal panama.” No idea where that came from. It was just the magic of the moment. It killed.

Whatever form or vehicle we used for performing improv on stage, once we had the format and structure settled, we were free to take it wherever we wanted and however guided by the audience. This was completely liberating and allowed us to successfully add improvisation to our show to the extent that for our last few years together, we were mostly doing just the improv and very few, if any, sketches. But the prep work ahead of time in determining the structure of the bit and how we’d work together to pull off whatever it would become each show was no less important.

Kinda fitting that in our early days, we’d just be riffing late at night on the couch and an idea would pop out that we’d meticulously script, rehearse, and perform on stage with great fanfare and bravado only to close out our years as a comedy troupe coming around full circle to agreeing to the rules of a few improv games we’d created ahead of time and knowing how to work together to then go out on stage in front of an audience and wing it with abandon.

So, if water is life, then improvisation is structure.